Arab Jerusalem

The following remarks were presented by the Institute for Palestine Studies’ General Secretary Walid Khalidi at Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies’ symposium on “Arab Jerusalem.” Khalidi’s description of Israeli exclusivist ambitions over Jerusalem were remarkably prescient and his words are even timelier today. Below is an abridged version of the presentation and the full remarks may be read here.

. . . Today, the basic concept that seems to inform all discussion on Jerusalem is that of the “unity of Jerusalem.” In principle, the concept sounds worthy of the Golden City and its ecumenical significance to humanity.

On closer scrutiny, however, a different reality emerges. Sixty-six percent of so-called “united Jerusalem” is territory seized by force in 1967. Of that, 5 percent is what had been the Jordanian municipality of Jerusalem and 61 percent is West Bank territory annexed into the Jordanian municipal area. Before 1948, Jewish land ownership in that 66 percent was less than 3 percent. Even the Jewish Quarter of the Old City was Jewish primarily in tenancy; most of the quarter belonged to old Jerusalem families as waqf (Islamic endowments).

As for the remaining 34 percent of “united Jerusalem” that is today’s West Jerusalem, Jewish-owned property there before 1948 did not exceed 20 percent overall; the rest belonged to Christian and Muslim Palestinians and to international Christian bodies. This sector contained the most affluent Palestinian residential quarters as well as most of the Palestinian commercial sector.

This West Jerusalem also included the lands of the occupied or destroyed villages of Dayr Yasin, Lifta, Ayn Karem, Maliha, Romema, Shayka Badr, and Khallat al-Tarha. Most of the Israeli government buildings in this area, including the Knesset, are built on Palestinian land. Thus, the great bulk of “united Jerusalem” is, quite simply, conquered and arbitrarily expropriated land.

In terms of the population in this “united Jerusalem,” some 170,000 Jews now live in settlements established in those parts of Jerusalem seized in 1967, whereas only about 3,000 Jews had lived in those same areas prior to 1948. In contrast, to this day virtually no Palestinians are allowed to live in West Jerusalem, whereas more than 35,000 fled or were expelled from that part of the city during the 1948 fighting and thereafter. This figure includes the inhabitants of the villages just mentioned, which were incorporated in the West Jerusalem city limits after 1948.

Nor are the current municipal borders of Jerusalem the limit of Israel’s ambitions for Jerusalem. Israel has already surrounded East Jerusalem with concentric rings of colonies on West Bank territory outside but contiguous to the municipal borders of the city. The plan, already well advanced, is to integrate these colonies with united municipal Jerusalem in order to create Greater or Metropolitan Jerusalem. Under Likud, this plan will be pressed forward at an even more frenetic pace than under the Labor government. The resultant Metropolitan Jerusalem will cover twice the surface area of present-day municipal “united Jerusalem.” A great advantage and indeed the prime objective of this strategy for Israel is that the more Palestinian territory that is alienated from the West Bank in the name of Metropolitan Jerusalem, the less the physical, political, and psychological space that will be left for the Palestinians there in the West Bank. One can count on Netanyahu to carry this strategy to its very farthest extent. . . .

The area of David’s ancient capital per se constitutes less than 1 percent of today’s so-called united Jerusalem. No religious, historical, economic, or security considerations informs the extended municipal boundaries of East Jerusalem, much less those of Metropolitan Likudist Jerusalem. What does inform them is ruthless gerrymandering in the service of solipsistic nationalism and a spirit of defiance of world opinion. . . .

The proposition of a clash of civilizations, far from being the latest in prognostication, is old hat. Remember Rudyard Kipling with his “East is East and West is West and ne’er the Twain shall meet”? But the proposition itself is not harmless old hat. It is tendentiously deterministic and ominous in its self-fulling potential. Its deepest flaw is that it abolishes human initiative. That is why a viable solution for Jerusalem must steal the thunder of all irredentists – of Crusades and proxy-Crusades, of jihads and counter-jihads.

That is why all those committed to an honorable and peaceful solution must band together to stop in their tracks the forces of fundamentalism – Muslim, Christian, and Jewish – slouching towards their rendezvous in Jerusalem. . . .

* * *

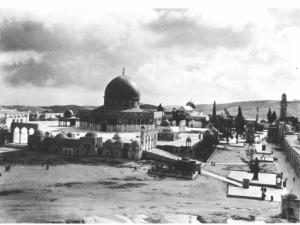

For our February Special Focus – Arab Jerusalem, we are highlighting a series of articles from the Journal of Palestine Studies as well as from the Jerusalem Quarterly, the only journal exclusively dedicated to the city's history, political status, and future. Selected are contributions from, inter alia, Edward Said, Ian S. Lustick, and Rashid Khalidi on Jerusalem's Arab heritage and fate under Israeli occupation. All photographs are from Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians, 1876-1948, by Walid Khalidi.

Journal of Palestine Studies:

Dividing Jerusalem: British Urban Planning in the Holy City

Dividing Jerusalem: British Urban Planning in the Holy City

Nicholas E. Roberts

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Summer 2013), pp. 7-26

British administrators employed urban planning broadly in British colonies around the world, and British Mandate Palestine was no exception. This article shows how with a unique purpose and based on the promise of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, British urban planning in Jerusalem was executed with a particular colonial logic that left a lasting impact on the city. Both the discourse and physical implementation of the planning was meant to privilege the colonial power’s Zionist partner over the indigenous Arab community.

Fieldnotes from Jerusalem and Gaza, 2009–2011

Fieldnotes from Jerusalem and Gaza, 2009–2011

Elena N. Hogan

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Winter 2012), pp. 99-114

Written by a humanitarian aid worker moving back and forth between the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem over a two-year period (May 2009– June 2011), the observations in these “fieldnotes” highlight the two areas as opposite sides of the same coin. Israel “withdrew” from Gaza and annexed East Jerusalem, but both are subject to the same degree of domination and control: by overt violence in Gaza, mainly by regulation in East Jerusalem.

Salvage or Plunder? Israel's "Collection" of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem

Salvage or Plunder? Israel's "Collection" of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem

Gish Amit

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Summer 2011), pp. 6-23

During April–May 1948, almost the entire population of the residential Arab neighborhoods of West Jerusalem fled the fighting, leaving behind fully furnished houses, some with rich libraries. This article is about the “book salvage operation” conducted by the Jewish National and University Library, which added tens of thousands of privately owned Palestinian books to its collections. Based on primary archival documents and interviews, the article describes the beginnings and progress of the operation as well as the changing fortunes of the books themselves at the National Library. The author concludes with an exploration of the operation’s dialectical nature (salvage and plunder), the ambivalence of those involved, and an assessment of the final outcome.

The Christian Churches of Jerusalem in the Post-Oslo Period

The Christian Churches of Jerusalem in the Post-Oslo Period

Michael Dumper

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Winter 2002), pp. 51-65

This article surveys the main trends in the relations of Jerusalem's historic churches with Israel and the Palestinians since the 1967 occupation and especially since Oslo. It examines the shift from cooperation with the Israeli state in the early period to a closer identification with the Palestinian nationalist position under the impact of Israeli actions and other factors, including pressures from the laity and an increasingly "Palestinianized" higher clergy, and details the growing cooperation among the churches themselves. The article ends with an examination of the various options for a future church role, especially in the light of the churches' proposal for a "special statute" for Jerusalem, and concludes that a holy place's administrative regime under Palestinian sovereignty would be more likely to protect long-term Christian interests.

The Centrality of Jerusalem to an End of Conflict Agreement

The Centrality of Jerusalem to an End of Conflict Agreement

Rashid Khalidi

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Spring 2001), pp. 82-87

More than any other issue of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, Jerusalem has deep resonance for all the parties. Certainly, there will be no end to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, no Arab-Israeli reconciliation, and no normalization of the situation of Israel in the region without a lasting solution for Jerusalem. For a solution to be seen by all parties as satisfying, it must accomplish three things: it must allow Palestinians and Israelis to share the city equitably; it must allow Jerusalem to be the capital of both Palestine and Israel; and it must allow people of all faiths to have free and unimpeded access to Jerusalem.

Yerushalayim and al-Quds: Political Catechism and Political Realities

Yerushalayim and al-Quds: Political Catechism and Political Realities

Ian S. Lustick

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 5-21

Israel's insistent portrayal of "Yerushalayim" as "united and indivisible" and as encompassing not only all of Arab al-Quds but vast surrounding areas had a crucial political purpose: to block any negotiated settlement with the Palestinians by creating a taboo against even discussing any separation. The campaign was successful in some ways but ultimately failed as a hegemonic project. This failure is reflected in the Barak government's willingness to reimagine the city's future. This article examines four misconceptions about Israeli attitudes toward Jerusalem and its status in Israeli law. In so doing, it documents the potential for Israeli flexibility on the issue.

The Ownership of the U.S. Embassy Site in Jerusalem

The Ownership of the U.S. Embassy Site in Jerusalem

Walid Khalidi

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 80-101

One of the most difficult issues of the final status negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians is Jerusalem. The complexity of this issue has been compounded by U.S. actions to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and by allegations that the prospective site of the embassy is Palestinian refugee property confiscated by Israel since 1948.

The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947-50

The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947-50

Nathan Krystall

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Winter, 1998), pp. 5-22

This article describes the progressive depopulation of the Arab neighborhoods of West Jerusalem following the outbreak of the fighting in late 1947. By the time the State of Israel was proclaimed on 15 May 1948, West Jerusalem already had fallen to Zionist forces. Quoting from eyewitness accounts, the author recounts the widespread looting that followed the Arab evacuation and the settlement of Jewish immigrants and Israeli government officials in the Arab houses. By the end of 1949, all of West Jerusalem's Arab neighborhoods had been settled by Israelis.

For Arabs Only: Building Restrictions in East Jerusalem

For Arabs Only: Building Restrictions in East Jerusalem

Sarah Kaminker

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Summer, 1997), pp. 5-16

Government planning policy denies Palestinians the right to use their land in East Jerusalem. Thirty-three percent of this land has been expropriated and used for building homes for more than 40,000 Jewish families. Planning schemes confine Palestinians to 10 percent of the land area of East Jerusalem. Draconian bureaucratic measures imposed on "Arabs only" aggressively prevent construction on the remaining Palestinian lands in East Jerusalem. The result: a shortage of 21,000 homes for Arab families. Using Har Homa to provide for the Arab "homeless" could be the only political and moral justification for developing the lonely mountain Jabal Abu Ghunaym.

Edward W. Said

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 5-14

Israel was thus able to project an idea of Jerusalem that contradicted not only its history but its very lived actuality, turning it from a multicultural and multireligious city into an "eternally" unified, principally Jewish city under exclusive Israeli sovereignty.

Israeli Settlement in the Old City of Jerusalem

Israeli Settlement in the Old City of Jerusalem

Michael Dumper

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Summer, 1992), pp. 32-53

Since 1967, Israeli settlement policy in Jerusalem has been directed towards a single overriding goal: the consolidation of Israeli control over Palestinian East Jerusalem in order to prevent any future redivision of the city. In political and functional terms, this has involved declarations of a "united" Jerusalem as the "eternal" capital of the Israeli state, combined with the transfer of government offices and the extension of municipal authority and services to East Jerusalem. Demographically, it has meant strenuous efforts to construct housing and encourage the settlement of Israelis in the Palestinian parts of the city.

From Palestinian to Israeli: Jerusalem 1948-1982

From Palestinian to Israeli: Jerusalem 1948-1982

Ibrahim Matar

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Summer, 1983), pp. 57-63

Since 1948 the city of Jerusalem has undergone a process of "Israelization" accomplished by the uprooting and dispossession of the Palestinian Christian and Muslim population. This displacement of Palestinians from the Holy City was achieved by two methods. First, the use of a terror campaign in 1948 to evict the Palestinians from their homes and villages in what is now called West Jerusalem. The second method utilized a legal process, developed after 1967, by which privately-owned Palestinian land was confiscated for "public purposes." "Public" refers to the Israeli public, and the "purpose" is the establishment of exclusive Jewish residential fortress colonies being built in East Jerusalem.

Wall Politics: Zionist and Palestinian Strategies in Jerusalem, 1928

Wall Politics: Zionist and Palestinian Strategies in Jerusalem, 1928

Mary Ellen Lundsten

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 3-27

Exactly 50 years ago, late in September 1928, an "incident" occurred at the Western Wall of the Holy Sanctuary in Jerusalem which set in motion a sequence of violent events that clearly "vibrate," as Croce put it, in political situations and judgments today. The Western or "Wailing" Wall controversy, which became a public issue in 1928, triggered the intercommunal violence that in 1929 claimed 800 casualties and marked the shift of the political process in Palestine into the irreconcilably violent phase which continues today.

S. Abdullah Schleifer

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Autumn, 1971), pp. 68-86

Monday morning, June 5, 1967. At 0850 an Aide-de-Camp called the Palace in Amman to report to King Hussein Radio Cairo's communique that Israel had attacked Egypt. By 0900 the Egyptian General Abdul-Moneim Riad - who had arrived in Amman with a small group of staff officers to take command of the Jordanian front a few days before the war began - had received a coded message in Amman from UAR Field Marshal Amer. The UAR, the message said, had put out of action 75 per cent of the Israeli planes that had attacked the Egyptian airports and the UAR Army, having met the Israeli land attack in Sinai, was going over to a counter-offensive. "Therefore Marshal Amer orders the opening of a new front by the commander of the Jordanian forces and the launching of offensive operations according to the plan drawn up last night."

Jerusalem Quarterly:

Jerusalem: Five Decades of Subjugation and Marginalization

Nazmi Ju'beh

Jerusalem Quarterly 62 (Spring 2015)

Two Letters from Jerusalem: Haunted by Our Breathing

Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Sarah Ihmoud

Jerusalem Quarterly 59 ( 2014)

Pockets of Lawlessness in the "Oasis of Justice"

Candace Graff

Jerusalem Quarterly 58 (Spring 2014)

The Jerusalem Master Plan: Planning into the Conflict

Francesco Chiodelli

Jerusalem Quarterly 51 (Autumn 2012)

The "Center of Life" Policy: Institutionalizing Statelessness in East Jerusalem

Danielle C. Jeffe

Jerusalem Quarterly 50 (Summer 2012)ris

Edward Said's Lost Essay on Jerusalem: The Current Status of Jerusalem

Edward Said

Jerusalem Quarterly 45 (Spring 2011)

Talbiyeh Days: At Villa Harun ar-Rashid

George Bisharat

Jerusalem Quarterly 30 (Spring 2007)

Documents and Source Material:

Walid Khalidi

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Autumn 2012), pp. 71-82

EU Heads of Mission, Report on East Jerusalem, Jerusalem, 10 February 2012 (excerpts)

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Spring 2012), pp. 223-32

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Spring 2011), pp. 206-08

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Winter 2011), pp. 195-202

Ir Amim, Analysis of the Jerusalem Master Plan 2000, Jerusalem, June 2010

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Autumn 2010), pp. 193-96

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Autumn 2007), pp. 88-110

Documents Concerning the Status of Jerusalem

Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Autumn, 1971), pp. 171-94

Research and scholarship requires investment. Generous contributions from people like you allow us to provide invaluable resources as a public good. Make a tax-deductible donation today!

Projecting Jerusalem

Projecting Jerusalem The Fall of Jerusalem, 1967

The Fall of Jerusalem, 1967